|

| Eileen Flanagan |

Download MP3 [29:31]

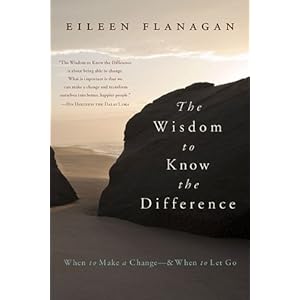

Most episodes of the Social Work Podcast take huge topics - like stigma, suicide, and cognitive-behavior therapy, and try to distill them into 30-minute overviews. Today's podcast flips that on its head. Today we're spending over thirty minutes to unpack 25 words. My hope is that listeners learn something about the Serenity prayer - something that they can incorporate into their social work education or practice. In today's social work podcast, I spoke with Eileen Flanagan, author of the award winning book, The Wisdom to Know the Difference: When to Make a Change-and When to Let Go

And now, on to Episode 61 of the Social Work Podcast: The Wisdom To Know the Difference: an Interview with Eileen Flanagan.

Bio

Eileen Flanagan is a writer and teacher whose work helps people to live with less anxiety. Her newest book, The Wisdom to Know the Difference: When to Make a Change-and When to Let GoTranscript

Jonathan Singer: Eileen thanks so much for being here, and talking with us today about the Serenity Prayer, about the wisdom to know the difference, and my first question for you is, in the introduction to your book, you talk about the origins of the Serenity Prayer, and you included an earlier version that's different from the one most people know, and I was wondering if you could read the earlier version, and just talk to us a little bit about how this version, the early version, gives us insight into the meaning of the more commonly known one.Eileen Flanagan: Sure, well first thanks for having me here. And why don't I read both so that your listeners can hear the difference themselves. The first one that I learned and the one that most people know goes like this, "God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can change, and wisdom to know the difference." Now as I started doing research on this, I found out that the prayer was originally written by Reinhold Niebuhr, whose a protestant theologian, at first people thought he wrote it in the '40s but now they've dug up even earlier versions, and he probably wrote it in the '30s although it was the '40s when it became famous, and the version that his daughter sites in her book on the prayer goes like this, "God give us grace, to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things that should be changed, and wisdom to distinguish the one from the other."

Jonathan Singer: So those do sound different.

Eileen Flanagan: They have a kind of different style and tone, but some of the subtle changes also can shift the meaning. One of the words that usually jumps out as being different is the "should," and I sometimes give weekend retreats and, will give people the two versions of the prayer and ask them to reflect on which one speaks to them, and it's very interesting how people respond to the word "should," there are some people who feel very, beaten down with "shoulds" in their life; "I should eat less sugar" "I should exercise more" "I should not spend so much time reading e-mail at work" and so they hear that word "should" and they rebel against it, and they say I don't need anymore "shoulds" in my life, I don't want some prayer telling me what I "should" do. It's interesting because, Niebuhr was, very concerned with social justice issues, he was speaking during World War II, he was very outspoken about racism and anti-Semitism and poverty, and so when I hear the "should," I hear, the societal "shoulds," for him we should address segregation in the south, we should address poverty, and that to me has a different kind of connotation, it has a challenge in it, but not so much nagging, more the possibility that we might be able to change things that we don't think we can, and so I always think of the Civil Rights Movement, at the time Nieburh read this prayer, he could not have imagined the changes that would happen in the next 20 years, although he felt we should change those things if the metric had been, can we change it? I don't think people would have bothered trying, you know what I mean? The Montgomery Bus Boycott, when it started had no idea what it would lead to, they really did not think they would accomplish what they did, and so to me that word "should" can be, an opening of possibilities, rather than a limitation. But if we're speaking about our own lives, you know, sometimes the word "can" is more helpful, so different versions of the prayer might fit different situations. The other thing I'd point out about the difference, is that the most common version is in the singular, God grant me to change what I can change, and that version is sometimes said in the plural, in the recovery movement, but the Niebuhr version is definitely in the plural, and so that again shifts the meaning a little bit, you know, are we focused just on my own life, which is a very appropriate use of the prayer, but I think it can also apply to those bigger things that might be able to change together, which neither of us could change by ourselves.

Jonathan Singer: So it sounds like, the more common version of the prayer is really, a personal, version and the earlier version that you read, was really intended as a communal thing, what can we do, what should we do as a community.

Eileen Flanagan: Yeah, and I can't I'm an expert on Niebuhr's intentions, but that's how I hear it from the bit I know about his life. I think both have a communal aspect, because he was a preacher giving sermons, so he was addressing a community, and in AA community is really important or in every recovery movements, the community is very important but it is more focused on changing individual lives rather than changing social structures, for example. The third difference that I would point out is that Niebuhr's version says, God grant us grace, and then the other things are off shoots of grace, whereas the recovery prayer, or the prayer that's more commonly used just says, God grant me serenity and courage, and, both of them start with God, but it makes sense to me that the recovery movement uses, just God, and not God grant me grace, which to me, anyway has a more Christian connotation, it has a more specifically religion, we're depending on God for all of this kind of connotation, and I think one of the things the recovery movement has been so successful at, is opening up spirituality, to say, we believe in something bigger than ourselves but we don't care what you call it, you know, we want to welcome everybody, you figure out what this word God means to you, but we're not trying to limit anyone's understanding of that, and so that reference to a higher power can be an invitation rather than again sort of a scolding, you have to buy into this theology, whereas I think the word “grace”, some people love the word “grace” but for other people it has baggage. So it makes sense to me that that word got dropped as the prayer [chuckle] got more popular.

Eileen Flanagan: Yeah, and I can't I'm an expert on Niebuhr's intentions, but that's how I hear it from the bit I know about his life. I think both have a communal aspect, because he was a preacher giving sermons, so he was addressing a community, and in AA community is really important or in every recovery movements, the community is very important but it is more focused on changing individual lives rather than changing social structures, for example. The third difference that I would point out is that Niebuhr's version says, God grant us grace, and then the other things are off shoots of grace, whereas the recovery prayer, or the prayer that's more commonly used just says, God grant me serenity and courage, and, both of them start with God, but it makes sense to me that the recovery movement uses, just God, and not God grant me grace, which to me, anyway has a more Christian connotation, it has a more specifically religion, we're depending on God for all of this kind of connotation, and I think one of the things the recovery movement has been so successful at, is opening up spirituality, to say, we believe in something bigger than ourselves but we don't care what you call it, you know, we want to welcome everybody, you figure out what this word God means to you, but we're not trying to limit anyone's understanding of that, and so that reference to a higher power can be an invitation rather than again sort of a scolding, you have to buy into this theology, whereas I think the word “grace”, some people love the word “grace” but for other people it has baggage. So it makes sense to me that that word got dropped as the prayer [chuckle] got more popular.Jonathan Singer: So it’s interesting because, it sounds like the earlier version, is much more about, what should we as a Christian community do, to, improve the world, and the Serenity Prayer as is commonly used today, in the recovery movement, it, intentionally avoids saying, this is a Christian thing, and says, more what can I do, what can I understand about what I can control, what I can’t, and how can I make changes in my life.

Eileen Flanagan: Yeah that’s how I hear it, how can I make changes with the support of my community, and it’s interesting how, that word “God” still has a religious connotation to some people but the way AA and other recovery groups use it, has opened it up. One of the people I interviewed is a Buddhist, who’s been in recovery for 20 years, and so he talked about how, okay, so this is not my language, you know a lot of these things are still from the Judeo Christian tradition even if people think they’re not, it feels very Judeo Christian to me but it’s open enough that I can bring my Buddhist understanding to it, and I can see the way that these words apply, to my life and my understanding of spirituality.

Jonathan Singer: So in your book, “The Wisdom to Know the Difference,” you really unpack, the Serenity Prayer, and, I was wondering, if you could talk a little bit, about, for the people that you interviewed, how would they go about, identifying the things that they couldn’t change, and then, how do they go about accepting them.

Eileen Flanagan: Well I think it depends a lot on the person, and the situation, there are some situations where it’s clear that you’re not going to be able to change, something, but coming to acceptance might be an internal process, you know of, coming to peace with that, and that’s another thing about the word “acceptance,” you can accept it in a, superficial way without really being at peace with it, and, and again that gets into the question of injustice too, you don’t have to be happy about everything that you accept, for example one of the people I interviewed, her son was killed in Iraq, well, she accepted that that’s what happened, but that doesn’t mean she’s got to be happy about it. The word doesn’t necessarily have to have that connotation. But in another way, when we talk about letting go, which is one of the chapters in the book, we are talking about coming to peace with something, and so there were some cases, where, that was really a choice, is someone gonna accept the fact that her husband left her with a young child, for example is one of the people I interviewed, and that she’s not going to be able to convince him to come back and she should really stop trying because that’s not helping anything. There’s that kind of situation, there’s, the situation of one the most traumatic stories for me of letting go, of a man I interviewed named Dan Gottlieb, who is an author and Philadelphia radio talk show host, and when I had first started hearing him on the radio I didn’t realize that Dan had been paralyze in a car accident 30 years ago, from the waist down, and he talked about how he was really forced to learn to let go, this was not a choice, let me be at peace with my situation it was thrust on him, and he had to deal with that, and, went through many difficult years, struggled with depression, lost his wife and his best friend in the process, had a lot of health issues that continue because of his paralysis, but what helped him, come to, more peaceful place in his life, was learning actually about Buddhist meditation and mindfulness, and the idea of being present to what is, and appreciating what is instead of always having your mind focused on what you wish things were. So one of the, stories he tells that really has helped me probably more than any other, story in the book, is he talks about the picture, and how we often have a picture in our mind of how things should be, and he tells this story of a woman, who got married and she had this picture of what her perfect husband should be, and then he wasn’t that, and so she was disappointed, and then, other things happened that weren’t her picture of her life and she was disappointed, and then she thought, well my daughter’s getting married that will make me happy, but that guy wasn’t the picture either, and at the end he says, she says she’s had a miserable life, and he says, the problem was the picture, nothing else, that she couldn’t really appreciate these people in her life because she was measuring them against, whatever kind of myth she had in her mind, and I find that that is really true in big things and in small things, the only choice left to me is, am I going to have a good attitude about it, or a bad attitude about it, and there’s some situations where that ‘s really clear, I can’t stop the snow, there are a lot of other situations where it gets much more murky, and having difficulty in a relationship at work, or with someone in my family, in those cases the line between what do I need to accept, and what do I need to change can get a lot more blurry.

Jonathan Singer: So it makes sense that one of the ways people can accept things is by, figuring out what vision they have, in their mind for how things should be, and then, really just getting in reality with how things are.

Eileen Flanagan: Yeah and I would say paying attention to the stuff in our mind is a key in lots of ways, so knowing what my picture is, and when I need to let go of it, is one thing, another is knowing, myself and my social conditioning, my, personal strengths, I think, one of the things that’s interesting to me about the prayer is a lot of people tend to find one line, more difficult than the others, I think that some people grow up in ways that they sort of expect the world to fall into line with their expectations, maybe they’ve had a privileged background or a family that catered to them or whatever, and so when they hit a situation, where, they don’t’ get their way, it’s excruciating, it’s really hard then to accept, those things, whereas there are a lot of other people who, don’t get their way very much as children, live in a world that is clearly not in their control, especially if you grow up you know in a dysfunctional family or something where there’s lots going on that you have no control over, you might grow up used to being powerless, and for that person, taking the initiative to change something that they could change, if they took proactive steps, might be the thing that’s more difficult. So one of the things I talk about is reflecting on your life, and it could be influenced by your religious background, it could be your educational background, class, race, gender, generation, there’s lots of things that can play into it, and it’s very complex. I mean, for myself, I’m, a white middle class, person with an Ivy League education, but I’m also from a working class Irish family that has little fatalism running through it, and I’m a woman, and I can see how in different situations those different things influence me, what is more difficult for me, letting go, accepting, saying okay, I put this in the hands of some higher power, you know that person might need to learn, to step up a little bit more sometimes, or, there are other people who, for their growth as a person need to learn to let go and relax and say, okay I don’t need to control this.

Jonathan Singer: I really like this idea that, there are these different components of the Serenity Prayer and that, it might be easier, for somebody to accept the things that they cannot change, whereas for other folks, letting go, or accepting that you don’t have control, would be the challenge, and so I was wondering if you, if you could share a story about somebody who gained the courage to change.

Eileen Flanagan: Sure, one of the stories I tell in the book is of a woman named Hillary Beard who was stuck in a job that she really found dissatisfying. She was probably maybe around 30 when she started thinking about wanting to change careers, she could spend 30 more years being really miserable doing something really boring, and she’s a very smart person, who, could have done a lot of other things, but she was very scared to make a change, and so she talks about some of the things that helped her, and I’ll just outline a couple of them. One was changing her assumptions about what was possible, and she gives the very specific example of, being a black woman who wanted to become a writer, and, realizing that her father, who, had been very successful who was one of the first African American city planners of his level, in his city, had, trained his kids like, this is what you need to do to be successful in American, and one of the things he had said when she expressed an interest in a creative career early on, was, black people can’t succeed at that, you’re a black woman, go into business you know, this is the route for you, and so she had followed that advice, and then she describes, it was in the early ‘90s having this experience of turning over three different books. She found one by, Alice Walker, one by Terri McMillan, and one by Toni Morrison, and here on the back of each one was this big beautiful picture of a black woman, and Hillary describes, having this moment of realizing that thing that I believe isn’t true anymore, and she makes a point that it wasn’t that her dad was giving her bad advice, I mean he came up in a very rough time, and there’s still racism in the publishing industry, but this limit that she thought was impermeable, clearly had shifted, and so that was the moment when she, found the courage to go start taking writing classes, because she said this, this barrier isn’t there anymore and I shouldn’t let the barrier in my mind stop me. The other things she did, and she says that this is one of the things she got out of Corporate America is knowing how to make a plan, [chuckle] and how to set goals, she gathered a few other people, in her work environment who also wanted to make a career change, and they would meet over lunch, on a regular basis, and support each other, so first of all she had community, but they also supported each other in setting very specific goals; where do you want to be in five years, so imagine it, and then, write down what you need to do to get there, and part of what I love about this story is there’s been all these books about the Law of Attraction, and thinking positively, and there really is something to that, but I think that if you think of it as magic, I’m just gonna, imagine where I want to be in five years, that is not really what works. [laughter]

Jonathan Singer: Right, you can’t visualize, changing careers and then have somebody say, Oh my goodness, Hillary, let me offer you the career you want!

Eileen Flanagan: Yeah and actually, when you get on your path sometimes those miraculous things happen, I’m a Quaker and we use the term, “Way Opening,” that when you are making those steps in the right direction, sometimes, you do get the call out of the blue, which Hillary did actually, but you don’t get the call out of the blue until you do some ground work. You can’t just imagine being a writer and then expect to get the call, so what Hillary did was she made these very specific steps that she would have to take, and she said that she was terrified, partly because, her father was a very strong, positive figure in her life, but this meant going against, what her father’s advice was. So it was very frightening, for her, and so she would do a little thing each day. She said, one day she would bring her telephone book into work, this was back when people actually used telephone books [chuckle] to look things up, so she brought a telephone book into work one day. The next day she went through and she circled or made a list of all the colleges that might offer, a continuing ed class, that’s a little thing, I can do that it’s not too scary. The next day she called, each of the places on the list and asked for a catalogue, that’s a little thing that not too scary. And she said that by breaking it down into doing at little thing every day, suddenly she’s enrolled in a writing course and she said that was scary but by then, she was excited because she had taken all these little steps.

Jonathan Singer: Yet she had been successful, she had set out short, measurable, achievable, objectives, and she had done them, and so by the time she had gotten into the classroom, she’s like, oh I can do this cus I did those things.

Eileen Flanagan: Right, exactly. So, she gets great feedback on her writing in the writing class. She decides to attend a writer’s conference, and she lays out all these little things that she did, she started writing articles because, she had corporate experience there were some, writing opportunities that came to her that helped her build her experience, so that by the time she takes the big leap, to become a full-time writer, she does get a miraculous call, I mean you joked about no one’s going to call you, someone called her out of the blue and asked her to co-write a book on values with Venus and Serena Williams.

Jonathan Singer: The tennis champions.

Eileen Flanagan: Yes! That was one of her first books, she has now written seven books I think, a few of them are best sellers, so the call out of the blue does happen, but she did an awful lot of leg work. There are a lot of other threads to Hillary’s story but, I think those things of having community, setting measurable goals, and paying attention to your thinking, can all be really helpful when someone is trying to make a scary change.

Jonathan Singer: And one of the things that I got out of what you said is that, the courage to change, is incremental. So we’ve talked, thus far, about, granting me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and now, [chuckle] we’re at the title of the book, and the last line, and, how do people know the wisdom to know the difference? To know the difference between what they cannot change and the things they can change.

Eileen Flanagan: Well one of the things I like about that earlier version of the Serenity Prayer, is the line, “the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other,” which is a much less catchy book title, [laughter] and so I like “The Wisdom to Know the Difference” as a title, but the word “know,” makes it sound like something definite and final, and “distinguish” is more of a process, and it is an ongoing process of learning what we can and cannot change, so some things that help people, to develop that wisdom, one I think is learning from your mistakes. Psychologists have tried to come up with, a definition of wisdom that everyone can agree on, and they can’t, but there are some things that they agree, are qualities that wise people share, and one of them is that they learn from their mistakes, and so I found that as I was looking for people to interview, I tended to start with older people, and, what I realized is that you can live a long time and not learn from your mistakes so it’s not that, being 80 automatically makes you wise, but if you learn from your mistakes and you live to 80 you probably will have [chuckle] accumulated, some wisdom along the way. And one of the things that those people often talked about was accepting themselves, knowing themselves, and accepting themselves, and that that relieves an awful lot of anxiety. If you’re not trying to be someone other than who you are, if you know what your strengths and weaknesses are, it’s just easier to navigate the world, and you have less stress about impressing people, or trying to be what, they want you to be, so those are some things that I think can help people. Along with the self knowledge I would say that thing I mentioned before of reflecting on what’s your own background, what are the ways you’ve been conditioned, just so you have that awareness, in the way that Hillary realized, I was taught something by my family, that was a really helpful tool, to my parent’s generation but doesn’t fit me anymore, so having that reflection on your own life, can be really helpful, in, learning wisdom, or developing wisdom, another key I would say is community, in fact community I think helps in all three lines of the Serenity Prayer, if you’re dealing with something really difficult, having people around to support you, is going to be key, but also if you’re trying to change something scary, like Hillary gathered those other people at lunch who had similar goals, community can be really important in that, but it can also help you in the distinguishing. I think, well one example is, an artist who was unhappy with her agent, and was complaining to her friends year after year, and it was the friends who said, you know you’ve been saying the same thing for three years now, and it was having someone else reflect that back, they weren’t telling her what to do, they were just, observing, sometimes that can be really helpful, in letting us see ourselves. And the last thing I would bring it back to, that idea of some kind of higher power, the book draws on a lot of different spiritual traditions, and you don’t necessarily have to be a religious person I think to find benefit in the Prayer and, this way of thinking, about what you can and cannot change, but certainly for many people, part of the Prayer is the idea that there is something bigger than myself that I can lean on, in difficult times, and that can help guide me, and so some of the people talk about, learning to listen to the wisdom within themselves, paying attention to that inner voice, and trusting that it is connected to some bigger source of wisdom in the Universe, and so some of the stories are really about learning to listen to that, and finding that that little voice inside you really knows, what the right thing to do is in a certain situation, but in a busy world with cell phones and TVs and the internet going all the time we don’t always listen to it, and so making space in your life, for self reflection, for mindfulness or meditation, or for listening to that voice within, can all be very helpful.

Jonathan Singer: Well Eileen thanks so much for unpacking the Serenity Prayer for us today, I know that I loved your book and I found your words today to be thought provoking and inspiring and, I hope that listeners out there felt the same way, if you did, you can go to our Social Work Podcast website and leave your comments, or you could go to the Social Work Podcast page on Facebook, at www.facebook.com , and then search for Social Work Podcast, and I also hope that, in contrast to some of the big ideas that we talk about on the Social Work Podcast, that it was an interesting journey for you the listener to have these few words unpacked in such rich detail, so thanks again Eileen I really appreciate it.

Eileen Flanagan: Thank you very much for having me Jonathan.

--End--

References and Resources

Eileen Flanagan's website: http://www.eileenflanagan.com/

Hilary Beard's website: http://www.hilarybeard.com/

Dan Gottlieb's website: http://www.drdangottlieb.com/

APA (6th ed) citation for this podcast:

Singer, J. B. (Host). (2010, September 19). The wisdom to know the difference: Interview with Eileen Flanagan [Episode 61]. Social Work Podcast. Podcast retrieved Month Day, Year, from http://socialworkpodcast.com/2010/09/wisdom-to-know-difference-interview.html

No comments:

Post a Comment